|

Pitcairn's

Seventh-day Adventist Church |  |

By

Herbert Ford, Director

Pitcairn Islands Study Center We know there was

religious practice on Pitcairn long before the coming of the Bounty sailors and

their companions in the late 1700s. We don't know much of anything about the type

of religious practice of pre-mutineer times, unless we can presume that it closely

followed that of the Polynesians to the north and west of Pitcairn, or perhaps

even some of the people from the east. However there was

much evidence found on the island in earlier years of religious artifacts and

implements. Unfortunately most of it has been destroyed or otherwise lost. Once

Fletcher Christian and his companions began their occupation of Pitcairn religion

seemed to play only a small and insignificant role in their lives.But, again,

unfortunately, little is recorded for us about the first two decades of Pitcairn

life after the occupation by the mutineers.  | Celebration

inside Pitcairn's Seventh-day Adventist Church |  |

It

was not until the rather strange and marvelous life change that came to John Adams

that religion seems to have become a significant part of Pitcairn life. Once he

had decided that religion held the promise of a better life for the little colony

on the island, Adams lost no time in implementing what we would call strict religious

practice. Sir Charles Lucas, editor of The Pitcairn Island Register Book,

describes the coming of religion to John Adams' life well in his introduction

to the book. "Many notable cases of religious conversion have been recorded

in the history of Christianity," writes Sir Lucas, "but it would be

difficult to find an exact parallel to that of John Adams.

The facts are quite clear. There is no question as to what he was and did after

all his shipmates on the island had perished. He had no human guide or counselor

to turn him into the way of righteousness and to make him feel and shoulder responsibility

for bringing up a group of boys and girls in the fear of God. He had a

Bible and a Prayer Book to be the instruments of his endeavour, so far as education,

or rather lack of education, served him. He may well have recalled to mind memories

of his own childhood, But there can be only one simple and straightforward explanation

of what took place, that it was the handiwork of the Almighty, whereby a sailor

seasoned to crime came to himself in a far country and learnt and taught others

to follow Christ.

And earlier in his introduction, Sir Lucas

puts the unusual-ness of the whole matter in almost dramatic perspective:

In order to fully appreciate the Pitcairn story, it is necessary to keep before

the mind's eye the contrasts which it presented. What could be more remote from

the murders and crimes of the early years upon the island than the settlement

as it developed under John Adams, in peace, godliness and comparative innocense.

Or, again, contrast the day-to-day life of this tiny, isolated group of human

beings, as it flowed on in even monotony, with the wars and rumours of wars and

great events which in the same years stirred the whole outside world. Pitcairn

might have been on another planet!

| |

|

| |

John

Adams |

So it was that from shortly after the turn

of the century until his death in 1829, John Adams was Pitcairn's strong religious

advocate and mentor, as well as its civil leader. Some folk, stretching things

a bit I think, have suggested that Adams was pretty much a dictator. There is

not a great deal of fact to back up such contention though. According

to the Reverend Thomas Boyles Murray, John Adams observed the rules of the Church

of England; always had morning and evening prayers; and taught the children the

Collects, the Catechism, and other portions of the Prayer-book. He was particular

in hearing the children say the Lord's Prayer and the Apostles' Creed. And, it

seems Adams was a popular religious teacher, too. Murray writes that Adam's

youthful pupils took such delight in his religious instructions that on one occasion,

on his offering to two of the lads--Arthur Quintal and Robert Young--some compensation

for their labor in preparing ground for planting yams, they proposed that instead

of his giving them some gunpowder as a present, that he should teach them some

extra lessons from the Bible--a request with which he joyfully complied, says

Murray. Adams early religious background was part and parcel of his work-house

upbringing in England where he would have undoubtedly been exposed to some of

the rites and ceremonies of the Church of England. Relying on these childhood

memories, it is understandable that at times his recollection or understanding

faltered, or that he tended to extremes in biblical exegesis. The church's injunction

to fast on Ash Wednesday and Good Friday was transmuted by Adams on Pitcairn into

a prescription of weekly Wednesday and weekly Friday fasts, much to the discomfort

of his flock. Only after the arrival of John Buffett in 1823 was Adams

"set straight" on this point about the fasts, but in spite of this he

still continued the Friday fasts--every Friday! Adams' particular construction

on the prohibited degrees in marriage, might well have saved the community from

extinction. The table of kindred and affinity in the Book of Common Prayer that

spoke to this matter was thankfully often ignored. Nevertheless, certain Levitical

laws, such as those requiring abstention from unclean birds, were observed.

In these more permissive views of his about marriage between "relatives"

to achieve what Adams considered good purpose, he may have inadvertently set the

stage for practices on Pitcairn, the unfortunate result of which the Island has

even in recent years experienced. But the piety that Adams instilled in

the Pitcairn community was to become legend world-wide. That this should be so

is all the more amazing considering that all of the other adults, up to the arrival

of Buffett, Evans and Nobbs, were Polynesian. Being in the majority, and also

being the mothers of the community, the Polynesian women were in a strategic position

to foster the tenets of their own faith on Pitcairn. By the time George Hunn Nobbs

arrived though, Christian services had developed to such an extent that "Island

visitors wavered between boredom at their length and repetitiousness, and awe

of what they were witnessing." The devout religious attitudes and

observances of the Pitcairners--reported to the outside world by captains, crews

and passengers of ships calling at the island--set loose a wave of approval so

forceful that it only intensified the piety and religiosity of those on the island.

Raymond Nobbs says "What was reported from Pitcairn about the Islanders'

piety and faith served as a powerful argument in support of some of the most cherished

tenets of both organized religious institutions and believing individuals."

Here then--on tiny, remote Pitcairn Island--was living, flourishing proof of the

efficacy of the Christian ethic and the salvation which lay in the Gospel in religious

attitudes and observances: this people all around the world came to believe. And,

as word came back to the Pitcairners of the admiration the world had for their

piety, their reaction was to increase their Christian virtues, asking repeatedly

for more religious instruction for the people. These repeated requests of the

Pitcairners for a clergyman to teach them the way of righteousness are a matter

of record in numerous letters we've examined in Honolulu, Sydney, Wellington and

London. A few of the sincere calls for spiritual guidance are also on file in

the Pitcairn Islands Study Center. When Captain William Waldegrave, along

with his chaplain, arrived at Pitcairn in the Seringapatam in 1830 with

supplies for the islanders, this is the reported conversation that took place:

"I have brought you a clergyman,” said Captain Waldegrave. "God

bless you," issued from every mouth, "but is he come to stay with us?"

"No." "You bad man, why not?" from the people.

"I cannot spare him, he is the chaplain of my ship, but I have brought you

clothes and other articles, which King George has sent you." "But,"

said Kitty Quintal, "we want food for our souls!"

In 1840 the London Missionary Society ship Camden, with Captain Morgan

in command, called at the island. The Reverend Mr. Heath and the Captain went

ashore with presents from the Governor of New South Wales, the Lord Bishops, and

the Reverend D. Ross. Mr. Heath preached a most impressive sermon which the Pitcairners

listened to with breathless attention. And Captain Morgan spoke to them on "The

Care of the Soul." But after three impressive services during the day and

evening the Camden spread her sails, beat to windward, and was lost over

the horizon. The ongoing watering of their souls which the Pitcairners so earnestly

desired was once again denied them.

There is no doubt that the

piety of the Pitcairners was genuine. When the French Consul Morenhout visited

the island, his feeling about the Pitcairner's piety was determined by an episode

which took place when he was put to bed in the same room with some of the islanders.

After they thought him asleep, the elders woke everybody but the Consul and said

their prayers on their knees. Morenhout, who was awake but pretending sleep during

the prayers, was deeply impressed.

| The

Bounty Bible (AKA the Pitcairn Bible)

is part of the Pitcairn Island

Museum's collection. |

While their adherence to Christian

values remained strong while in their Island home, the move of all on Pitcairn

to Tahiti in March of 1831, proved to be the undoing of much that the people had

learned of the Christian way. What was seen in Tahiti--and yielded to by some

while there--had its unfortunate effect once the Pitcairners returned to their

homeland. "The godly discipline established by Adams had been sadly

sapped," says one writer of the Pitcairners' short stay in Tahiti. "The

ancient still of the Bounty which was used for making alcoholic drink once

again appeared and 'seethed devilishly'. It had been said that 'the Pitcairners

of those earlier days never really forsook the habits of the Tahitians'."

Certainly the demoralizing atmosphere of Papeete began to have an effect once

the people had returned to Pitcairn. And it was in Tahiti that the Pitcairners

learned racial prejudice, something they had never thought of before. Among those

of lighter skin there came to be a hatred of the Black people. Into the

vacuum after Tahiti came a character to Pitcairn life who was a dictator in the

real sense of the word--one Joshua Hill. A recital of his devastation and demoralization

of the Pitcairn spirit will serve no good purpose here. He attempted to be both

religious and civil leader of the Island, and on the religious side of things,

about the only good deed he did was to destroy the old still and thus thwart the

often unbridled use of the kickapoo joy juice that was brewed in it. With

Hill's departure from Pitcairn, George Hunn Nobbs, who had taken on the role of

Pitcairn's pastor, was to become an effective religious leader. In 1850 the Pitcairners

began to add harmonious music to their religious services through the teaching

of Hugh Carleton, a gifted musician who was one of those stranded on Pitcairn

when the bark Noble sailed off and left them. By 1852, Pastor Nobbs

was able to enhance his religious leadership of the Island considerably when through

the courtesy of Admiral Fairfax Moresby he was able to go to London and there

be ordained as a minister of the Church of England. For four years, thereafter,

until the departure of the Pitcairners for Norfolk Island, the values of true

religion were again evident in abundance on Pitcairn. Back on Pitcairn

again after their stay on Norfolk Island, the band of those who chose to return

continued practicing the Church of England principles they had faithfully followed

under the leadership of George Hunn Nobbs. All attended weekly worship services,

with Moses Young acting as host. The services were enhanced by Young's musical

solos on the fife and violin, instruments he had learned to master under Hugh

Carleton's direction in 1850. In 1860, HMS Calypso called at the

Island to show the flag of Mother England. The ship's chaplain came ashore and

spent several hours in religious instruction of the children. But Pitcairn had

to continue without a religious leader, even though their calls for someone to

lead them in Godly ways continued through the 1860s and into the 1870s.

One day in March 1876, the ship St. John, made a call at Pitcairn that

was to eventually change the religious persuasion of the Island. Captain David

Scribner went ashore, along with "a beautifully-toned Mason and Hamlin Organ

which the Pitcairn men shouldered up the Hill of Difficulty to the village. Once

in place in the thatch-roofed Island church, the good Captain sat down at the

organ and led the Pitcairners in a stirring rendition of the old gospel hymn 'Shall

We Gather at the River?'" Among the many other gifts Captain Scribner

brought onto the Island that March day was a large box of Christian literature

- literature printed by those of the Seventh-day Adventist faith. It had been

brought to the San Francisco docks and put into Scribner's hands by two Seventh-day

Adventist ministers living in California's Napa Valley: James White and John Loughborough.

After the St. John sailed onward toward Cape Horn and her destination

at Liverpool, England, the Pitcairners studied the literature Captain Scribner

had brought. They noted that it said the Adventist faith calls for worship on

the seventh-day of the week as counseled in the Bible. And they noted that the

Adventists believed in the return of Jesus to Earth a second time--the Second

Advent they called it. The name of their faith--"Seventh-day" and "Adventist"--came

from those two important aspects of the Christian faith, the literature said.

But the Picairners were content in their Church of England practice at the time,

and the literature was set aside. A decade passed, and then in 1886 Pitcairner

Rosalind Young, the daughter of Island leader Simon Young, one day happened upon

the literature. She found a tract entitled "The Sufferings of Christ,"

and found it of such interest that she encouraged her father to read it. He did

and was so interested in what he had read that he encouraged others to read the

various tracts. Alta Hilliard Christensen in her book, Heirs of Exile,

says of the spread of a new gospel: At first the Pitcairners

read the papers with extreme care and suspicion, as though they were afraid of

being entrapped, but when they found that every doctrine presented was given on

Biblical authority their fears subsided. The more they studied the more interested

they became. . . . Although nearly every one of them felt an inner conviction

on the matter, no one had the courage to break away from the established custom

and begin the observance of a different day of worship.

An

interesting historical footnote to the idea of the Pitcairners changing their

day of worship from Sunday to Saturday, the week's seventh day, is that from the

time the Islanders began their adherence to the principles of the Church of England

under John Adams shortly after the 19th Century began and until 1814 when the

British warships Briton and Tagus called, they HAD been worshiping

on Saturday, even though they thought it was Sunday. The confusion had come when

the Bounty crossed the International Date Line coming eastward and the

adjustment needed had not been made. Thus the two days were confused until Captain

Staines corrected them when the two British ships chanced upon the Island in 1814.

| |

|

| |

John

I. Tay |

And now, in addition to this new reading

of Bible principles by most of the Islanders, there came to their rocky shores

an American seaman named John I. Tay, who would help solidify their feeling that

a change in their worship should happen. Tay, who spent many years at sea on several

ships, had more recently retired in Oakland, California. He had become convinced

of the value of the Seventh-day Adventist faith, but of late had began languishing

in health. On his doctor's advice that he should move out of the polluted air

atmosphere of Oakland, Tay put to sea again in an attempt to regain his health.

At the same time he was eager to tell others the principles of the faith he had

come to love. Having read the story of the Bounty mutiny and its aftermath,

he determined to tell the Pitcairners about his faith. His journey to Pitcairn

is an interesting one but time does not permit a recounting of it just now.

Once he arrived at Pitcairn, by permission of the islanders, Tay stayed on the

island for five weeks in October and November of 1886 studying the Bible with

them. By the time he sailed from Pitcairn on the yacht General Evans, the

majority of those on the island had decided to become Adventists. They asked Tay

to baptize them into the new faith, but he explained that only an ordained clergyman

could do that, and he was simply a layman. But he promised to return with an ordained

minister.

|

|

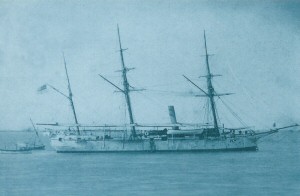

Layman John Tay arrived at Pitcairn Island in 1886 on the British warship, HMS Pelican, Captain R. W. Hope

(Courtesy of David Ransom, Maurice Allward Collection)

|

|

Two years later Tay attempted to fulfill his promise, but the

affair ended in a maritime disaster. Then in 1890 he was able to keep his word

with the calling at Pitcairn of the Adventist missionary ship which was appropriately

named Pitcairn. Almost all of those on the Island chose to be baptized.

A number of

the islanders, caught up in the love of their new faith just as John Tay was,

decided to carry word of the Adventist faith to other islands of the Pacific Ocean.

The missionary ship Pitcairn called first at the Island on each of its

six voyages into the Pacific from San Francisco, and several times Pitcairn Islanders

left the Island on it to carry the Christian gospel elsewhere. Several of the

Pitcairners, feeling the need for advanced education, came to the United States

on the missionary ship where they studied at Healdsburg College in Northern California,

the forerunner school of Pacific Union College where the Pitcairn Islands Study

Center is now located. [Read more about

the connection between Pitcairn and Pacific Union College.]

|

|

| |

Seventh-day Adventist schooner Pitcairn |

Through

the years of the 20th century the practice of their Adventist faith brought joy

to many Pitcairn hearts and Christian comfort to countless others. The long tradition

of the singing of hymns of the Christian faith from their longboats by the Pitcairners

at the departing of each ship from the island has been a treasured expression

of their faith. It has drawn favorable even passionate comment by hundreds of

ship captains, and not a few from passengers and crew members.

In her article

in the Eastern Horizon magazine in 1980, Molly G. Elliott describes the

effect of the Pitcairners' religious faith and their singing of it when she was

a passenger on the Mataroa which called at the Island:

Once alongside the Mataroa, the Pitcairn people swarmed up the ship's ladders

amid bursts of unlaced laughter. Tall, dark, biscuit-skinned, they have perfect

teeth, and charming old-world manners. No one wore shoes. Even though, like most

New Zealanders, I go barefooted around the home in summer, I had never seen feet

like those--gnarled, the toes splayed and almost prehensile. They brought

aboard palm-leaf kits filled with bananas, oranges, pawpaws, pineapples and carvings

of flying fish and tortoises and boxes in the shape of an open Bible. Unlike souvenir

traders on other Pacific islands, they did not solicit custom with a beggar's

cajoling whine. Nor did they permit haggling. As we had arrived on Saturday,

the islanders refused to trade on this, their Sabbath. We could take what we wanted

and make a donation. One woman distributed Seventh-day Adventist literature.

When the ship's siren boomed an all-ashore signal, the islanders tumbled down

the ladders, those extraordinary toes gripping strongly. They rowed away

to a safe distance and then, their boats rising and dipping on the slow, grey

Pacific swells, they sang in perfect unaccompanied harmony, the old hymn 'Shall

We Gather at the River?'

"I had seldom heard such moving

singing," Ms. Elliott writes. "Absolutely silent, passengers and seamen

clustered along the rail, many with brimming eyes. Then the ship swung away, the

women waving as the men bent stoutly to the oars, judging to a whisker the channel

between the rocks into Bounty Bay." The long-lasting, positive effect

of hearing the Pitcairners sing of their Christian faith to passing ships is even

more clearly illustrated by Fred Duncan in A Deepwater Family, published

in 1969. The son of Captain F. C. Duncan of the three-skysail-yard ship Florence

which called at Pitcairn in 1895, Fred Duncan was then just a boy. Over half a

century later he wrote about the call of his father's ship at Pitcairn and of

the hymn singing of the Pitcairners: Two big longboats rowed

out to us and their crews came aboard. As it was late in the afternoon, time was

short and trading was brisk In order to avoid the danger of being set too near

the shore by the current, the ship was kept under shortened sail, and we started

to draw away from the island. As twilight began to make its outline in

the distance, the island leader came to the cabin to say farewell. Noticing the

little cabinet organ, he asked my father if his men could sing to us. They were

given an enthusiastic invitation to come in and soon our little room was crowded.

Without any introduction they swung vigorously into the familiar hymns of the

Moody and Sankey era, roaring out the refrains with a power that held us, and

with a Polynesian rhythm that was irresistible. They particularly liked

a hymn titled 'God Is Calling Yet': 'God is calling yet, you hear 'em,' they roared,

and excitement mounted like that at a revival meeting. By the time the final hymn

was finished and the last of our friends slid down the line to his boat, a light

mist lay low over the water. Moonlight gave the scene unrealistic loveliness,

which was heightened as the boats pulled off into the haze by the rhythmic splash

of oars, their rattle against thole pins, and the repeated diminuendo choruses

of 'God is Calling Yet'--'God is calling yet, you hear 'm, God is calling yet.'

"I was only eight years of age at the time," wrote Fred Duncan, as an

old man, "but it was a spiritual experience that has lived through a lifetime."

The commendable and beloved practice of the singing of Christian hymns to passing

ships has been somewhat forgotten on Pitcairn Island today. It has been replaced

usually only by the singing of the plaintive Pitcairn "Good Bye Song."

In the passing of that practice, I am afraid that something of great value has

died or is dying on Pitcairn Island.

As with all religious persuasions,

the Adventist faith has not been an absolute shield against the anti-social or

lawless actions of a very few on Pitcairn. The 1897 murder of his wife and child

by Pitcairner Harry Albert Christian, an Adventist young man overcome by lust

and passion, is but one example of how religion, while it is the power of God

unto salvation, is only so to those who place their complete and daily trust in

the power of the divine.

In recent years religion of any persuasion has

declined on Pitcairn. In mid-2005 fewer than a dozen of the 50 or so people on

the Island were members of the Adventist faith. A significant number of others

espouse no specific religious faith at all. Any assessment of the good or ill

the practice of religious faith has had on the Pitcairn people through its two

centuries of present habitation is largely in the eye of the assessor.

I believe that the adherence to the Biblical principles of both the Church of

England and the Seventh-day Adventist faith by those Pitcairners who have been

faithful to the heavenly vision has had a decidedly salutary effect on Pitcairn

life. Ever since those early years of the 1800s, when John Adams, "a sailor

seasoned to crime, came to himself in a far country and learnt and taught others

to follow Christ," Pitcairn Island, the "Rock of the West" has

been a better place for it. Missionaries

and Resident Pastors of the

Pitcairn Island Seventh-day Adventist Church | 1886

- | John

I. Tay | 1890 - | John I. Tay | 1890

- 1892 | John Melville Marsh | 1890

- 1894 | Edward Harmon Gates | 1893

- 1896 | Hattie

Andre | 1894 - 1896 |

G. W. Buckner | 1896 -1898 | Jonathon

C. Whatley | 1895 - | Edwin

Sebastian Butz | 1901 - 1903 | Griffiths

Frances Jones | 1907 - 1912 | Mark

Warren Carey | 1910 - | Rosalind

Amelia Young | 1913 - 1917 | Melville

Richard Adams | 1924 - | Robert

Hare | 1933 - 1934 | William

Douglas Smith | 1938 - 1939 | Alfred

George Judge | 1938 - 1944 | Frederick

Percival Ward | 1943 - 1945 | Donald

Henry Watson | 1944 - 1949 | Evelyn

Rachel Totenhofer | 1947 - 1951 | Frederick

Percival Ward | 1953 - 1955 | Norman

Asprey Ferris | 1956-1959 | Lester

Norval Hawkes | | 1959-1960 | Rex Ewen Cobbin | 1959-1960

| Harold Albert Grosse | | 1961-1962 | Donald

Davies | | 1963-1964 | Walter Goeffrey Ferris | 1965-1966

| Leslie Allan James Webster | 1967-1968 | Walter

Goeffrey Ferris | 1969-1970 | Alfred J. Parker | 1971-1973

| Leslie Allan James Webster | 1974-1975 | John

James Dever | | 1976 | J. H. Newman | 1977-1979 | Wallace

Ross Ferguson | 1980-1981 | Oliver L. Stimpson | 1982-1983 | Thurman

C. Petty | | 1984 | Malcolm J. Bull | |

1985 | Leslie Allan James Webster | 1986

| Oliver L. Stimpson | 1987-1988 | L.

T. Barker | 1989 - | Kenneth Noel Hiscox | 1989-1992

| Rick B. Ferret | | 1993-1994 | Mark

N. Ellmoos | 1995-1996 | O.D. Brown | 1997-1998

| J. Y. Chan | | 1999-2000 | Neville

D. Tosen | 2001-2002 | John O'Malley | |

2003 | - | 2004-2005 | Lyle

Burgoyne | | 2006 | Michael F. Browning |

2007-2012 |

Ray

Codling |

2012 |

Paul Helling |

2013 - 2014 | Jean-Claude Honoura |

2015 |

Fredy Taputu, (Acting) Kean Dunstrom Warren |

Sequel to a Mutiny

By Dr. Milton Hook

Local maps of Pitcairn Island are always marked with odd names. For example, on the north coast are found places called "Where Dan Fall," "Johnny Fall," and "Where Freddie Fall." Pitcairners have a story attached to all these places.

The first Seventh-day Adventist church on Pitcairn Island.

Their folklore tells of past dramas when their ancestors met with disaster, scrambling after wild goats on the precipitous shore line. Other place names such as "Break 'im Hip," "Down Rope," "Stinking Apple," "John Catch a Cow," "Oh Dear," "Headache," and "Bitey-Bitey" carry reminders of the islanders history. "Down the god," in the northeastern sector, is another intriguing example, so named because it is the area where primitive hieroglyphics and art suggestive of heathen images can be seen in the rock face. These are token evidence that the island was inhabited at some time before the Bounty mutineers chose it as their hideaway.

The first Seventh-day Adventist church on Pitcairn Island.

Their folklore tells of past dramas when their ancestors met with disaster, scrambling after wild goats on the precipitous shore line. Other place names such as "Break 'im Hip," "Down Rope," "Stinking Apple," "John Catch a Cow," "Oh Dear," "Headache," and "Bitey-Bitey" carry reminders of the islanders history. "Down the god," in the northeastern sector, is another intriguing example, so named because it is the area where primitive hieroglyphics and art suggestive of heathen images can be seen in the rock face. These are token evidence that the island was inhabited at some time before the Bounty mutineers chose it as their hideaway.

In 1790 the mutineers, Fletcher Christian, Edward Young, John Mills, Matthew Quintal, William McCoy (or Mickoy), Alexander Smith (alias John Adams), John Williams, the American William Brown, and Isaac Martin, burned the Bounty off-shore. This effectively isolated them for eighteen years from the rest of the world, especially British retribution. In the meantime their criminal record was multiplied with murder and debauchery. Quintal and McCoy especially spent a great deal of their time drinking home-brewed alcohol they made from the roots of the ti-plant. Each mutineer had brought a Tahitian wife (more correctly, a mistress) with him. In addition they brought as servants four Tahitian men as well as two from Tubuai Island. One of the Tahitian men had his wife with him. Two single Tahitian women were also carried to Pitcairn and were shared by the other five Tahitian and Tubuan men. One little Tahitian girl from a previous marriage of McCoy's wife, made up the total of twenty-eight in their original company.

Trouble began when William's wife, Pashotu, slipped to her death from a cliff while gathering bird's eggs. Williams then assumed that is was his right to marry Toofaiti ("Nancy"), already wed to the Tahitian Talaloo. This was accomplished but "Nancy" was then kidnapped by Talaloo and his friend Oho. Another Tahitian, Menalee, pursued them and killed Oho and Talaloo on behalf of the whites. "Nancy" even turned on her husband and helped to slay him. The remaining native men retaliated a year later by murdering on the same day Williams, Christian, Mills, Martin, and Brown. A week later, in a fit of jealousy, Menalee shot fellow-Tahitian Timoa and fled to the hills where Quintal and McCoy were still in hiding. As soon as they found out that Menalee had shot Timoa, then McCoy, as retribution, shot Menalee. Young then realized they would be safe only if the remaining two native men were killed off also. Young's wife, Teraura ("Susan"), axed one of the natives to death and Young himself shot the other.

Pitcairn's Seventh-day Adventist church.

This murder spree of 1793 left only four white men on the island together with their wifes and children, as well as six widows, some of whom had children also. The men then took these more-than-willing widows as their mistresses. Near death with his excessive drinking, McCoy killed himself by jumping off a cliff three years later.

Pitcairn's Seventh-day Adventist church.

This murder spree of 1793 left only four white men on the island together with their wifes and children, as well as six widows, some of whom had children also. The men then took these more-than-willing widows as their mistresses. Near death with his excessive drinking, McCoy killed himself by jumping off a cliff three years later.

Tragedy replayed itself when Quintal's wife, Tevarua ("Sarah"), either committed suicide or fell accidentally from a cliff in 1799. Quintal then attempted to take a mistress of a fellow mutineer. In retaliation, Adams and Young axed Quintal to death while he lay in a drunken stupor. These two men then reflected seriously about their decade on Pitcairn and experienced a remarkable conversion. Their dramatic change of heart steered their history from its sordid past into an era of Christian commitment and service. They fossicked about and found Christian's Bible and Prayer Book. Young taught Adams to read and write because he knew he had but a short time to live, and Adams would have to take over the spiritual leadership. Young lost weight rapidly and suffered severe asthma. He passed away the next year (1800), leaving Adams with nine Tahitian women and twenty-three children from various unions, all now reformed in their habits. When the British rediscovered the settlement they were so impressed with the obvious change of heart they forgave Adams and let him live in peace.

During the 1820's John Buffett, John Evans, and George Nobbs joined the island community and married daughters of the mutineers. The entire population attempted to relocate on Tahiti in 1831. Soon after arrival they retreated in fright when fourteen of their number died of fevers with a three month span.

A successful migration was made to Norfolk Island in 1856, when the second penal settlement on that island was abandoned. The population of 194, including 107 children, consisted at that time of the Christian, Young, Quintal, McCoy, Adams, Buffett, Evans, and Nobbs families. The other names of the early settlers were not sustained in the family trees.

Many became unhappy with conditions on Norfolk. They yearned for the yams, coconut milk, and warmer climate of Pitcairn. A few adults were apparently upset at the thought of deceased relatives in untended graves on Pitcairn. Nostalgia overtook some of them, and eighteen months after their arrival on Norfolk they chose to break their family ties with the group and return to their beloved Pitcairn. Two married couples, all in their thirties, together with eleven children, were taken by schooner back to their homeland. The relatives who remained on Norfolk joined together to pay the fares.

Pastor Ollie and wife-nurse Yvonne Stimpson were Adventist missionaries to Pitcairn for three terms.

The male leaders who returned to Pitcairn were cousins. The group was made up of Moses and Albina or "Alice" (McCoy) Young and their four children, together with William Mayhew Young and his wife, Margaret (Christian) (McCoy), and their seven children. Among the latter's children were six from Margaret's first marriage to Matthew McCoy, who had accidentally shot himself in 1853 when firing the salvaged Bounty cannon. Thus, both the Young and McCoy families were represented among those who first returned to Pitcairn.

Pastor Ollie and wife-nurse Yvonne Stimpson were Adventist missionaries to Pitcairn for three terms.

The male leaders who returned to Pitcairn were cousins. The group was made up of Moses and Albina or "Alice" (McCoy) Young and their four children, together with William Mayhew Young and his wife, Margaret (Christian) (McCoy), and their seven children. Among the latter's children were six from Margaret's first marriage to Matthew McCoy, who had accidentally shot himself in 1853 when firing the salvaged Bounty cannon. Thus, both the Young and McCoy families were represented among those who first returned to Pitcairn.

A second homesick group of twenty-six returned in 1863 including another cousin, Simon Young and his wife Mary (Buffett/Christian). Others were Robert Pitcairn Buffett and his wife Lydia (Young), as well as Thursday October Christian II and his wife Mary or "Polly" (Young). Both women were sisters of William Mayhew Young who had been in the first returning group. The day before the second group sailed from Norfolk Island, Agnes Christian, daughter of Thursday October and "Polly" Christian, married Samuel Warren, an American on Norfolk. They made their home on Pitcairn too. Younger children in the Christian family who accompanied the group were Alphonso Downs Christian and Earnest Heywood Christian. These people later became Seventh-day Adventists.

By the time John Tay and other Seventh0day Adventist missionaries arrived aboard the missionary ship Pitcairn in late 1890, members of the Quintal family had also returned to Pitcairn Island. An entirely new surname was found too, i.e. the Coffin family. Philip Coffin had been shipwrecked on Ducie Island, one of the Pitcairn group, in 1881 with Lincoln Clark. After reaching Pitcairn Island, Coffin married Mary, a daughter of Samuel and Agnes Warren. Clark returned to America but came back a widower much later with his son, Roy, and both father and son married Pitcairners.

News of John Tay's initial evangelism on Pitcairn in 1886 and the Pitcairners abandoning of the Anglican rituals and Book of Common Prayer in 1887 soon became well known. One Anglican clergyman branded it "a religious debauch." Many wrote to the islanders trying to persuade them to reject Adventism. In letters, the Pitcairners themselves wrote to Tay it appeared some had the greatest difficulty accepting Adventist teachings on the state of the dead. However, all eventually fully agreed.

Among the first to be baptized as Seventh-day Adventists in 1890 were some still alive who had led the exodus back from Norfolk Island. These included Moses and Albina Young, then in their sixties. Another was Margaret (Christian) (McCoy) Young and some of her children from her first marriage, i.e., forty-five-year-old James Russell McCoy, Sarah (McCoy) Christian, Harriet Melissa (MCCoy) Christian, and their younger spinster sister Mary Ann McCoy.

Thursday October Christian II was the oldest one baptized among the initial group. He was over seventy years of age. The youngest baptized was ten-year-old Adelia or "Addie" McCoy. The following day, Sabbath, December 6, 1890, the Pitcairn Island church was organized. Simon Young and his son Alfred, were ordained as elders. Another son of Simon Young, Edward, as well as Daniel Christian were ordained as deacons. Edmund McCoy was chosen as church clerk. Rosalind Amelia Young, daughter of Simon Young, served as librarian.

The Pitcairners' long, rustic church in which they had previously met for their Anglican service was built of rough-hewn planks cut from the miro tree. The roof was a simple thatched one. Typically, no timbers were painted or oiled. At the door were tubs of water in which they washed their feet before entering.

On its return voyage from New Zealand in 1892, Pastor Edward H. Gates and his wife, Ida, disembarked from the ship Pitcairn to stay and minister to the infant Pitcairn church. While the ship was off Bounty Bay, Pastor Will Curtis, who was traveling to America, went ashore for the two-week stopover, and was impressed with the Pitcairners' Sabbath-keeping, hospitality, and communal spirit.

Members of the Seventh-day Adventist church on Pitcairn.

Curtis wrote in his "Bible Echo and Signs of the Times: of what happened when a fishing party returned with their catch. Some had caught many, others had just a few. But they all brought their haul to the public square and it was carefully divided up into twenty-four equal piles, representing the number of families on the island. Then one person turned his back on the fish while another pointed to each pile in turn calling out, "Here." Each time the one with his back to the fish responded by calling out the name of a family who then received that portion of the catch. In this manner food was shared without favoritism.

Members of the Seventh-day Adventist church on Pitcairn.

Curtis wrote in his "Bible Echo and Signs of the Times: of what happened when a fishing party returned with their catch. Some had caught many, others had just a few. But they all brought their haul to the public square and it was carefully divided up into twenty-four equal piles, representing the number of families on the island. Then one person turned his back on the fish while another pointed to each pile in turn calling out, "Here." Each time the one with his back to the fish responded by calling out the name of a family who then received that portion of the catch. In this manner food was shared without favoritism.

The Pitcairners' Sabbath School, Curtis described, began at 7:30 a.m., with singing and prayer before separating into various study classes. After this meeting they all went to breakfast and returned again for the 10:30 a.m., main service. Later, the 3 o'clock testimony meeting took place.

Hattie Andre arrived from America on the second voyage of the Pitcairn primarily to establish a better school. It was in that year (1893) that a typhoid epidemic took the lives of twelve people, and all Pitcairn families grieved the tragic loss. Andre and the Gates' drained their energies during the crisis while nursing the sick and comforting the bereaved. Edward Gates sunk so low in health that he and his wife were impelled to return to America when the Pitcairn called on its second return voyage in February 1894.

The third voyage of the Pitcairn (1894) brought a retired couple from America, W. G. Buckner and his wife, Rosa, to assist Andre. The first Week of Prayer on Pitcairn was held in the church over the Christmas period, December 22-30, 1894. Pastor Edwin Butz and his wife, Florence, arrived on the fourth voyage of the Pitcairn (1895). It meant that during their twelve-month stay there were five Adventist missionaries on the island. This was something unequaled either before or since.

Enthusiasm rose to new heights during the Andre/Buckner/Butz period. Plans were laid to make Pitcairn a focal point for training missionaries. Many Pitcairners themselves showed promise in this regard, and there was talk of bringing Tahitians to train at the school too. Three wooden buildings, each over eighteen metres long, were painstakingly constructed for these purposes at "Shady Nook," some distance from the main settlement. One was to serve as a classroom, the others as separate dormitories for girls and boys. Students lived at "Shady Nook" and were allowed to visit home for one hour each week, between six and seven on Thursday evenings. These strict measures were aimed at curbing alleged carelessness in eating and working habits among the islanders.

When the Pitcairn arrived from America in 1896 on its fifth voyage, the five missionaries on the island boarded for elsewhere, leaving the new missionaries, Jonathan and Sophia Whatley, to care for both the school and church work. All went well for twelve months, and then a dreadful crime dramatically altered the mission momentum. An unmarried young woman, Julia Warren, and her infant, were murdered by the child's father, Harry Christian. The victims' bodies were never found but Christian later confessed to cutting the woman's throat and throwing both mother and infant over a cliff into the sea. Christian was taken to Fiji, convicted, and hanged in October 1898. Pastors John Fulton and Galvin Parker were obliged to be present as witnesses and declared later that Christian died repentant and confident in Christ.

The crime sent shock waves reverberating around the world. Critics of Adventism made capital by spreading reports that despicable morals were rife on Pitcairn. The Pitcairn community itself was mortified because murder on the island had not been known since their pre-Christian days. Adventism's face blushed because the Pitcairn people, toted as the paragons of virtue and a model Christian society, had proved to be imperfect after all. The whole tragedy colored their history for years to come.

The heart-wrenching events of 1797-98 had their repercussions. They were a factor in church administration's rethink of the whole Pacific mission enterprise and the operation of the ship Pitcairn in particular. The crime also helped to remove the focus of attention to other island groups. The training school at "Shady Nook" became the playground of whistling winds. The Whatleys left early in 1898 and were not replaced. A permanent missionary-teacher for Pitcairn was not appointed until a decade later. Instead, various Pitcairn elders were ordained to lead the church. To their credit, Samuel Young, Alfred Young, Vieder Young, Benjamin Young, and Gerard Christian all took their turn at this responsibility.

During the period 1898 to 1907 the church members were visited by Adventist ministers on three occasions only. Gates spent three weeks on the island during the sixth and last voyage of the Pitcairn (1899). By 1902 Pitcairn and the Gambier Islands were considered to be children of the Tahitian Mission of the church. Griffith and Marion Jones worked in the area and stayed on Pitcairn for at least the first half of 1903. Pastor Benjamin Cady, the President of the Tahitian Mission, visited in November/December 1903.

The 1899 visit by Pastor Gates was marked by a religious revival in the wake of the Warren murders. Membership had slumped from the 1893 high of eighty-five to a low of sixty-six. The 1893 typhoid epidemic had accounted for some, but the reminder had been disfellowshipped for various reasons. Gates reported he baptized thirteen, some being rebaptisms.

This revival was followed by yet another in September when James Russell McCoy organized the first camp meeting on the island. He had attended similar camps in Australia and America and adapted these experiences to suit his homeland.

It does seem strange that people so isolated in the world should consider it necessary to seek further seclusion in the form of a camp meeting on the interior plateau of their island. However, camp meetings on Pitcairn became a regular feature. Twenty-two sleeping tents and two larger meeting tents were pitched, and the revival meetings were followed by the church elder baptizing twenty-four, seventeen being rebaptisms of folk who had either been disfellowshipped earlier or had felt guilty in some way for the wrongs in their society. Critics may question such rebaptisms, but the context of the situation (a deep seated remorse, the unspeakable shame, and even perhaps some adopted guilt) must be considered a powerful underlying reason. At the conclusion of the meetings, McCoy wrote, "Surely the face of the Lord is turned to us again…." In 1901 Commander George Knowling visited Pitcairn and reported, "The strong religious feeling which was once so marked a characteristic of the islanders appears—after the check it received a few years ago—to have again gathered strength.

When Pastor Gates had visited in 1899, he encouraged the church members to pay their tithe in the form of garden produce. This, in turn, had to be converted into cash. Therefore, a regular market was sought. "A small sailing craft is needed here," Gates wrote, "with which they can take their produce to the Islands of the Tuamotos…. Their soil is excellent, and with proper cultivation, would produce ten times as much as present. Plenty of hard work is a great preventive of evil practices." Gates obviously realized revivals and new resolutions may wane. He believed a practical remedy to prevent a repetition of the sorry 1897/98 episode was to kee the islanders busy.

Much of the Pitcairners' missionary zeal was without question. Leading members such as James Russell McCoy and his sister, little Mary Ann McCoy, joined the ship Pitcairn as soon as they were baptized and sought to witness wherever they could, especially among their relatives on Norfolk Island. During later voyages of the Pitcairn others sailed to distant islands as missionaries, including Maude, Sarah, and Maria Young. Special attention was given to the nearby Gambier Islands. One young woman in the first baptism, Adela Schmidt, originated from that group and she later married a Pitcairner. A few had come from her island of Mangareva to attend Andre's schools at "Shady Nook." But the boarding school closed, reducing the entrance of young people from abroad. Only the occasional one came for tuition. However, when young Lucas Cipreano of Mangareva fell to his death in 1900 while hunting goats on a Pitcairn cliff-face, the Gambiens were reluctant to send their children any more. Instead, Pitcairners tried living at Mangareva, a Roman Catholic stronghold, and operating an English-language school. However, these efforts did not generate a satellite mission.

From the time that Gates had suggested the Pitcairners seek markets for their tithe-produce, ways and means were explored to buy their own boat. James Russell McCoy found a trader friend on Mangareva who offered to help with a portion of the initial expenses, but the Pitcairners themselves found it difficult to raise the rest. Eventually, in 1902, the British Consul in Tahiti was given permission from England to loan the Pitcairners $436 to buy a cutter for trading between Pitcairn and Mangareva. They named her Pitcairn II.

Jones, then stationed in the Society islands, took on the task of sailing the Pitcairn II from Tahiti to Pitcairn and staying with it until the islanders themselves could learn navigation. The maiden voyage was the worst Jones had ever experienced. The crew consisted of six, but there was only accommodation for two. From the start they battled headwinds, high seas, and torrential rain. Their clothing was continually wet. They shivered and ached, and painful seawater foils broke out on their bodies. Jones was forced to crawl about on his hands because of a boil on his leg. Their fresh water supplies turned bad and they were reduced to a diet of dry biscuits. The trip, which normally took less than a week, extended to over a month.

Interior of Pitcairn's Seventh-day Adventist church.

At one stage they came close to Pitcairn but then were driven away near a dangerous reef and tossed about for another week. This was followed by a dead calm and they drifted even further away. Finally, Jones's navigational skills brought the boat to Pitcairn, and the taste of oranges again was like manna from heaven.

Interior of Pitcairn's Seventh-day Adventist church.

At one stage they came close to Pitcairn but then were driven away near a dangerous reef and tossed about for another week. This was followed by a dead calm and they drifted even further away. Finally, Jones's navigational skills brought the boat to Pitcairn, and the taste of oranges again was like manna from heaven.

For twelve months Jones plied between Mangareva and Pitcairn, trying to teach some of the men navigation. He had little success imparting his skills. Nevertheless, the boat was handed over to George Warren, one of the leading man on Pitcairn. Another twelve months later the boat was lost while the crew was riding out a storm off-shore. All had fallen asleep and the waves turned the boat over. Samuel Coffin drowned but the others struggled to shore. The British government graciously waived the loan, and in late 1906 a large cutter was purchased which the Pitcairners named the John Adams. It made one frightening return trip the following year, proving to be unseaworthy. It was resold at auction.

Under the leadership of James Russell McCoy, the Pitcairners ambitiously began building a new church as early as 1901. The local Miro hardwood had to be laboriously pit-sawn and carried down from the hills. By 1907 they had completed the two-storied nine-by-twenty-one meter structure resembling, in some respects, the Avondale (Australia) School chapel and classroom building. Upstairs was used exclusively for their church services. The downstairs section was used for Sabbath School purposes. Cady came from Tahiti, aboard the British man-of-war Torch, to dedicate the new church in June 1907. He stayed only four days while the ship anchored off-shore.

Cady brought with him a resident missionary-teacher, the first the Pitcairners had had for a decade. He was Mark Carey, a single man who originated from Tasmania, and had graduated from both the Missionary and Teachers Courses at Avondale. He had served for eighteen months in the Cook Islands. Traveling aboard the Torch, their cabin was so cramped Carey choose to sleep on the deck beside the gun even though salt spray and rain soaked him. Before Cady left, he ordained Carey as an elder to assist Benjamin Young in the new church.

The school was organized soon after Carey arrived, and he began in earnest with seventy-six pupils aged between six and thirteen. His insistence on punctuality, attendance, and adherence to a timetable proved to be too rigorous for the easy going Pitcairners. In the first twelve months, numbers dropped to forty-one in the morning sessions and only seven keen ones in the afternoon.

Another boat was purchased for the Tahitian Mission in April 1908, with the idea that it provide communication between Tahiti and Pitcairn, and accept cargo and passengers on a commercial basis to pay its expenses. It was a second-hand schooner of almost twenty-five tons and registered in Tahiti under the name Tiare, meaning "flower." It cost approximately $700. Most of the price was met from American and British donations, together with $200 from the Australasian Union Conference under whose control the boat remained. James Russell McCoy traveled on it as the ship's missionary, spreading literature among the Tubuan and Tuamotuan Island groups between Tahiti and Pitcairn.

When Pastor Frank Lyndon took over the leadership of the Tahitian Mission from Cady in 1910, he complained that the commercial interests of the Tiare absorbed too much of his time. Originally it was anticipated that the sale of Pitcairn's tithe-produce carried on the Tiare would reap handsome dividends. Curios and arrowroot were definitely shipped out, but the profit-and-loss statement by both the Pitcairn and Tahitian Missions, July 1908 to June 1910, show no evidence of increased tithe receipts. They may scarcely have met Carey's wages. Over all, the two missions were more than $3,000 in debt. Therefore, the decision was made to sell the Tiare. Once more the Pitcairners were doomed to extreme isolation, and much of the tithe-produce rotted on the island.

Other distressing aspects of the Pitcairn Mission became apparent. The membership figures of 1907-1910 showed a downward plunge. Emigration on the Tiare counted for some loss. Another factor was the absence of McCoy's strong leadership as he toured with the boat. Church administration voted to arrange the removal of the Pitcairners to Queensland but this was never carried out.

Carey was officially transferred to teach in the Society Islands in late 1910, but he failed to get a berth from Pitcairn until September 1912. Twelve months before Carey's leaving, the island was struck with its worst hurricane in living memory. At midnight flimsy houses began collapsing and others had to be roped down. Next morning, as the winds worsened, a major rescue was mounted to save the longboats relentlessly being swept out to sea. Then the school tumbled, and the court house. However, except for some iron sheeting coming undone on the church, that building stood. Later, Carey was obliged to conduct classes in the Sabbath School section downstairs until a new school was built.

As soon as it was certain that Carey had secured an exit passage, then arrangements were made for a replacement. Richard Adams, a West Australian, was just graduating in the 1912 class at the Sydney (Australia) Sanitarium. In December he married a 1911 graduate, Miriam Currow, and together they embarked for Pitcairn. It took them eight months to reach the island via Tahiti. Miriam wrote back to the homeland describing her terror when, six months pregnant, she had to clamber down the ship's rope ladder at the height of a storm and plummet into the longboat waiting to take them ashore.

The arrival of Adams was preceded by a camp meeting and a revival led by church leaders James Russell McCoy, Fisher Young, and Vieder Young. Once again many requested rebaptism. However, church records indicate that only new candidates, thirteen in all, were baptized by Adams soon after his arrival. Subsequent camp meetings brought further revivals, and by 1915 church membership figures had climbed back to about eighty once more.

Adams and Fisher Young led out as elders in the church, and taught school together even though neither was trained teachers. Pupils numbered approximately sixty. The Adams era was marked by rising optimism. No more talk was heard of mass emigration to Queensland. Renewed efforts were made to acquire their own boat and begin trading away their tithe-produce again.

Late in 1915 the decision was made to build a schooner from Pitcairn Island timber supplies. Some nails were forged from scrap metal. More were obtained as passing ships traded with them. Other supplies such as oil, robe, bolts, pitch, and other necessary equipment were also obtained by trading and donations. The completed boat was launched on January 15, 1917. They named her Messenger. It was smaller than the Tiare, measuring barely five-by-fifteen meters. Ten men, including Adams and the skipper, George Warren, set out for Tahiti immediately.

The Messenger reached Mangareva in four days. After doing some minor repairs they set sail for Tahiti. Two days out they ran into headwinds and tacked for three weeks. Then the winds increased to hurricane force, and for two days they were driven back half-way to Pitcairn. When it abated they decided, nevertheless, to press on for Tahiti and eventually arrived safely.

After the British Consul examined the boat, he forbade them to sail to Tahiti in it again. He feared for their safety, and advised they venture no further than Mangareva in the future. Lyndon, in fact, instructed Adams to transfer to Mangareva and only make periodic visits to Pitcairn. The reasoning was that the Pitcairners themselves could provide sufficient spiritual leadership and able teachers. Furthermore, Lyndon's aim was to establish a foothold in the Catholic bastion of Mangareva.

On its return voyage to Pitcairn in April the Messenger set out from Papeete with nineteen on board. After taking a buffeting for three days they were driven back to port with the foresail torn to shreds. A wealthy lady in Papeete saw their plight and bought them a new sail and ropes, throwing in a sack of sugar and another of beans. They set out again on May 4, arriving safely at Pitcairn exactly one month later, and finding that their distraught loved ones had virtually given them up as lost at sea. These experiences were typical of the continual battle the Pitcairners waged against the sea, the weather, and their isolation.

Adams never transferred to Mangareva becaue he and his wife returned to Australia in October 1917. It was another seven years before a replacement missionary came to live on Pitcairn. Several trips to Mangareva were made in the Messenger. After its maiden voyage to Tahiti borers began eating away at the timbers and much repair work below the waterline had to be completed. It was also damaged in a storm in 1919, then repaired , and re-launched early the following year. In March 1920, they sailed the vessel to Mangareva again where they loaded up with cargo and two horses for the return journey. After setting sail, they ran into fierce headwinds. Food and water ran low. The horses died and were tossed overboard, and the boat began to leak badly. Nearing Pitcairn a look-out on the cliff-top sighted them battling stormy seas. The longboats were sent out from Pitcairn to help but returned without locating the hapless seafarers. The following day they were located again but no one could control the boat to bring her in. A passing steamer came by two days later and the islanders rowed out and pled with the captain for help. He went back and tried to tow the Messenger but it began to break up. The seventeen people on board, including three women, two young girls and a little tot, were quickly transferred to the steamer and their little craft sank soon after. "Good riddance," said Fred Christian, "she was a terrible job, with a heavy nose, and she went just as fast sideways and forwards." It marked the end of mission boats for Pitcairn. From that time onward, missionaries and islanders alike depended on passing steamers.

The opening of the Panama Canal in 1914 caused many more ships to ply Pitcairn's waters, especially after war hostilities subsided in 1918. Between the two World Wars was the golden age for Pitcairn trading. It was the time when Pitcairn curios, hymn singing in the longboats, and friendly bartering with tourists, all became so familiar to the shipping companies and their passengers. The islander's fame as descendants of the Bounty mutineers, and the reputation built by their community, earned them world-wide admiration.

The hazards of trading with tourists were very realistic during rough weather. There was no safe harbor at Pitcairn. Bounty Bay was nothing more than a tiny inlet in a coast of rocks and cliffs. During bad weather the swell and pounding surf was both awesome and lethal. The Pitcairners had built a number of heavy longboats which they launched from a ramp and rode out to the ships through the breakers. The oarsmen had to be fit and possess more than just a streak of iron man in their sinews.

In the winter of 1921, during atrocious weather on one occasion, three longboats attempted to run the gauntlet of the boiling breakers and reach two ships off-shore. One ship, the Pitcairners knew, carried the High Commissioner of Fiji who had planned to visit among the islanders. Two longboats speared through the surf safely, but the third was carried back among the boulders. With great effort the men secured the boat with ropes while she was being tossed in and out with the breakers. The maneuvered her part way up the launching ramp, but just then a king wave struck the boat broadside and no hands could hold it. The boat rose and crashed repeatedly on every on-rushing breaker. Men slipped, fell, swam, stumbled, grappled, and grasped for breath in the alarming confusion. Three were badly injured. Sidney Christian lingered for three days between life and death but survived. Fisher Young was crushed underneath the boat, and as his uncle, Alphonso Christian, went to his rescue, he, too, was swept into the maelstrom. Alphonso died of severe head injuries soon after. Fisher lingered in agony with a broken back and internal injuries for two hours, his lips straining parting words about his beloved church, school, family, and God.

The tragedy dealt a severe blow to the entire community. Fisher Young had been their church elder and school teacher, accepting the leadership role when Adams left in 1917. Seventy-six-year-old James Russell McCoy was too old to take command again, and a vacuum developed in the spiritual guidance of the church members. This predicament became critical in late 1923 when David Nield, who had married Rosalind Amelia Young in 1907, visited Pitcairn.

Nield was known as a pastor of the Church of God and not sympathetic to the Adventist cause. He held such beliefs as a Wednesday crucifixion of Christ, the continuing necessity to celebrate the Passover, and the Edenic date-line theory which made Sunday the Sabbath in the southern hemisphere. He challenged the Pitcairners to give up Adventism and accept his teachings as his wife had done. Instead, the islanders refused and dispatched an urgent request to Australia for a resident Adventist missionary.

Their plea brought an immediate reaction. Pastor Robert Hare and his wife, Henrietta, were appointed to Pitcairn and arrived in late March 1924. Their ship arrived soon after Rosalind (Young) Nield had passed away. Her husband, after the funeral on the island, left on the same ship which brought the Hares.

Hare found the church in disarray. He set about its reconstitution and conducted revival meetings in the form of a Week of Prayer. Seventy-five renewed their covenant and were accepted into the reorganized church on the basis of their previous baptism. For the first time since Adams left they celebrated communion. Early in October, Hare held another revival during a camp meeting and sixty-five were baptized on two separate occasions, five of the candidates being re-baptisms. From its low ebb the fervor on Pitcairn soared to a high peak during those eight months in 1924. News then came to hand that Nield had died in New Zealand, and the Hares left Pitcairn on October 23.

No ministerial assistance was appointed to replace Hare. Once again the church members had to depend on leadership from within their community. Butz and his wife returned for eight months in 1929. Similarly, Pastor William Douglas Smith and his wife, Louisa, visited for the latter half of 1933. Each appointee had the task of injecting fresh spiritual life into the little community.

The Pitcairners' isolation naturally tended to foster loneliness as well as monotony in both church and everyday life. This was a recipe for discouragement and diminishing faithfulness in some hearts. For this reason the ebb and flow of church loyalty became a characteristic of many Pitcairn members. Nevertheless, a core of enduring believers continued, ministered by a succession of Australasian missionaries.

The advances of aviation and the subsequent decline in passenger shipping since the Second World War crippled the Pitcairners' trading practices. Many emigrated, becoming absorbed into the wider world. The relatively small group which continued on the island maintained their traditional identity.

This sequel to the Bounty mutiny continues to fascinate Christians and non-believers alike. The initiatives taken by the Spirit in the hearts of Pitcairners such as John Adams, Simon Young, Mary Ann McCoy, and many others remains a remarkable saga.

Major sources: 'Bible Echo and Signs of the Times,' the 'Home

Missionary,' the 'Advent Review and Sabbath Herald,' the 'Australasian Record,' the

Pitcairn Island Church Membership Record Book, Rosalind Young's 1894 book 'Mutiny

of the Bounty and the Story of Pitcairn Island, 1790 to 1894,' Harry Shapiro's 1929

genealogical research entitled 'Descendants of the Mutineers of the Bounty,' Robert

Nicolson's 1965 book 'The Pitcairners,' Richard Hough's 1972 book, 'Captain Bligh

and Mr. Christian,' and the author's personal collection of pioneer data.

Sources: Dennis Steley, Thesis

- “Unfinished: The Seventh-day Adventist Mission in the South Pacific, Excluding

Papua New Guinea, 1886 - 1896,” University of Auckland 1989. “Guide

to Pitcairn,” Pitcairn Islands Administration, 1999. Pitcairn Miscellany PISC files.

[Education][Medical] |